By Oliver Fischer

Nov. 6 2018

Ahmed Abdullah Al Fadaam, an assistant professor of communications at Elon University, shares his story of how he escaped the violence in Iraq in order to protect his family and pursue his passion for art.

By Oliver Fischer

Nov. 6 2018

Ahmed Abdullah Al Fadaam, an assistant professor of communications at Elon University, shares his story of how he escaped the violence in Iraq in order to protect his family and pursue his passion for art.

By Oliver Fischer

Oct. 15 2018

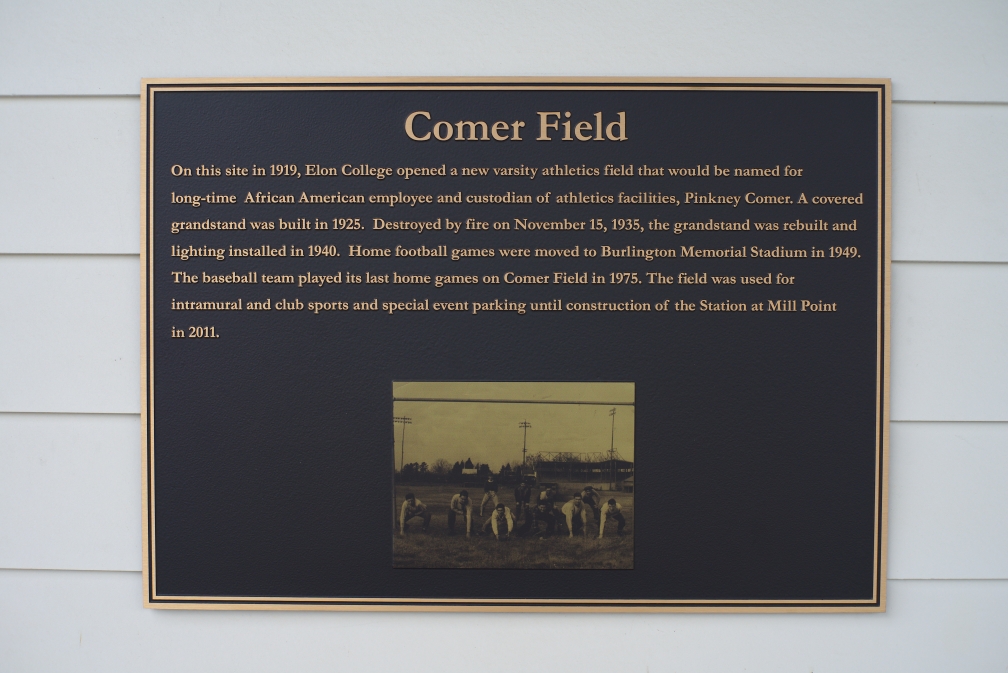

Seven new plaques have been installed around Elon’s campus this semester to commemorate historic sites or buildings that are no longer there. Browse the following map to take a closer look at all seven sites.

Business raise money using stocks and bonds, so any reporter covering business should be familiar with them. When an investor buys stocks of a company, they become a part owner of a small portion of the company. The price of a stock changes depending on the demand at the time. Wickham lists these typical sections of a stock published in a newspaper:

Bonds are essentially loans from an investor and corporations and governments use them to raise money. Unlike stocks, bonds are a low-risk investment and earn a set interest. The face value is the amount of money the owner will receive when it is mature. However, companies sometimes sell bonds before they are mature, so to calculate the current yield, Wickham offers this formula:

Current yield = (interest rate x face value) ÷ price

To calculate bond costs:

Bond cost (interest) = amount x rate x years

Indexes, such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average keep track of the price of certain stocks in order to provide an overview for investors.

Example problem:

John Smith paid $1500 for a bond with a $2000 face value and a 3 percent interest rate. What is the bond’s current yield?

Answer:

(3% x $2000) ÷ $1500 = 4%

Property taxes are the biggest income for local governments and they help pay for running expenses. For example, a city decides how much money they need and then they divide that number among property owners. Property taxes are measured in mills, which is 1/10 of a cent and Wickham says they are “expressed in terms of mills levied for each dollar of assessed valuation of property. Remember that the assessed and actual value can be different. Formula for mill levy:

Mill levy = Taxes to be collected by the government body ÷ assessed valuation of all property in the taxing district

The appraisal value of a property can depend on:

Assessed value formula:

Assessed value = Appraisal value x rate

Tax formula

Tax owed = Tax rate x (assessed value of the property ÷ $100) (if based on amount per $100 of assessed value)

Example problem:

What is the assessed value of a house appraised at $157.000 with a 25% appraisal value?

Answer:

$157.000 x 0.25 = $39.250

News stories often deal with directional measurements. They can provide more insight about people’s action and answer questions that readers may have. Being able to check these figures will lead to more accurate stories for your audience.

Formulas for distance, rate and time provided by Wickham:

Distance = rate x time

Rate = distance ÷ time

Time = distance ÷ rate

The difference between speed and velocity is that the latter indicates direction while the former doesn’t. The speed something is currently traveling when you take a snapshot of the moment is the instantaneous speed. Reporters are usually more interested in the average speech. To calculate acceleration, use this formula:

Acceleration = (ending velocity – starting velocity) ÷ time

Using the acceleration, you can find the speed at which a falling object hits the ground on earth.

Ending speed = √2(acceleration x distance)

Wickham defines momentum as the “force necessary to stop an object from moving. This is the formula:

Momentum = mass x velocity

Example problem:

The new Tesla Roadster can reach 60mph in 1.9 seconds. What is its rate of acceleration?

Answer:

(60mph – 0mph) ÷ 1.9s = 31.6 mph/s

Knowing how to express measurements can help with clarity in your stories. Often, analogies are useful for creating context and can help readers visualize measurements more easily. However, this only works when the reader understands the comparison and is also ineffective when exact numbers are needed (like number of parking lots).

These are formulas Wickham provides to different area measurements:

Perimeter = (2 x length) + (2 x width)

Area rectangle = length x width

Area triangle = ½ base x height

Area circle = π x radius²

Circumference = 2π x radius

Example problem:

A new parking lot is 200m wide and 300m long. What is the perimeter?

Answer:

(2 x 200m) + (2 x 300m) = 1km

Volume measurements play an important role when reporting about goods and provide additional context for articles. Wickham provides some common liquid measurements:

2 tablespoons = 1 fluid ounce

½ pint = 8 ounces

2 quarts = ½ gallon

1 U.S. barrel = 31.5 gallons

Volume of a rectangular solid:

Volume = length x width x height

The measurement for firewood is a cord. One cord equals 128 cubic feet when the wood is stacked in a line or row.

There are three different types of tons. They can be converted using the following table:

Example problem:

How many servings are there in 1 liter of orange juice?

Answer:

1L = 1000ml

One serving is 237ml

1000ml ÷ 237ml = 4.2

There are 4 servings.

The metric system is based on multiples of ten and is used in most places around the world. Journalists should know both metric and imperial to appeal to a wider audience and be able to interpret data, regardless in what form it is written. Wickham lists the prefixes and numerical values for the metric system:

Although Wickham provides conversion rates for most units, it is most practical to simply look it up when needed or to practice using the metric system to get a sense for the units, thus not needing to convert it in the first place. However, it is useful to keep these style rules in mind:

Example problem:

You are studying abroad in Denmark and the room you are in feels too cold. There is no thermostat because climate control is not used in most European countries, but there is a temperature sensor hanging on the wall. What value is it likely indicating?

Answer:

19°C or lower.

Numbers are omnipresent in journalism, even though one might initially think otherwise. From costs to test scores to budgets and emission values, many journalists don’t feel confident handling numbers, despite their integral role in reporting.

In her book Math Tools for Journalists, Kathleen Woodruff Wickham makes this clear in the first chapter. She calls the correct use of numbers a “sign of excellence and professionalism,” but warns that writers can still mislead or be inaccurate. Mathematical and numerical proficiency is necessary to check and understand the numbers in newswriting.

When using numbers for reporting, Wickham created a list with style guidelines. Some of the tips include:

Example problem:

If the road distance from Greensboro to Asheville is 180 miles, how long would it take to travel from Greensboro to Asheville if you drove at an average speed of 55 mph and traffic delays were 45 minutes?

Answer:

180 miles ÷ 55 mph = 3.27 hours

3.27 hours is about 3 hours 15 minutes. Adding 45 minutes results in a final time of 4 hours.

According to Wickham, percentages can help the reader understand the issues more clearly. To determine the percentage increase/decrease of something, use this formula:

(new figure – old figure) ÷ old figure

A typical application for this concept is salaries. Wickham offers the following formulas for calculating numbers revolving around salaries:

Original salary x percent increase = dollar amount of salary increase for first year

Original salary + salary increase = salary for the first year of the contract

First year salary x percent increase = dollar amount of salary increase for second year

First year salary increase = salary for the second year

Percentages of a whole put numbers into perspective. Use this formula to calculate and move the decimal points two points to the right:

Percentage of a whole = subgroup ÷ whole group

It’s important to distinguish between percentage and percentage points. If a the market share of a company for a product is 5 percent and goes down to 4 percent, it lost one percentage points but 20 percent market share. To calculate the points, simply add or subtract. For the actual percentage, see the percentage change formula from earlier.

Percentage calculations are commonly used in interests. Principal is the amount of money borrowed while money paid for the use of money is called interest. The percent charged for the use of money is the rate. Use this formula:

Interest = principal x rate (as a decimal) x time (in years)

According to Wickham, compounding is any interest added to the original principal. Any further compoundings are always added to the new value, not the original one.

To calculate the monthly payment on loans, use this formula:

A = monthly payment

P = original loan amount

R = interest rate, expressed as a decimal and divided by 12

N = total number of months

A = [P x (1 + R)^N x R] ÷ [(1 + R)^N – 1]

Example problem:

The local mechanic used to charge $85 for an oil change. Now they charge $122. By what percentage did the price increase?

Answer:

(122 – 85) ÷ 85 = 0.4353

The price increased by 44 percent.

Journalists often have to work with statistics and evaluate them. Be it crime rates, the average cost of food or or test scores. The mean, median and mode are three methods that a journalist can use to extract meaningful information from statistics.

The mean, often called the average, can be found the following way:

Add together all figures, then divide by the total number of figures used

The median is the number is the middle when arranged from the lowest to highest. If there is an even number of figures, use the two middle numbers and find their mean. Unlike the mean, the median is not affected by extremes at either end.

The mode is the number that appears most frequently in a set of numbers.

Wickham described the percentile as the “number that represents the percentage of scores that fall at or below the designated score.” It is based on the relationship to all the other scores. For example, if a test-taker had a score in the 75th percentile, 75 percent of other test takers scored the same or lower then they did. The formula is:

Percentile rank = (Number of people at or below an individual score) ÷ (number of test takers)

Number of people scored at or below that level = (Percentile) x (number of test takers)

Standard deviation indicates how much a figure deviates from the norm. A low standard deviation means that results are more consistent and vice versa. 65 percent of scores with data that has a typical distribution falls within one standard deviation (positive or negative). 95 percent fall within two standard deviations and 99 percent fall within three standard deviations.

Journalists rarely need to calculate the standard distribution but if they do, a graphic calculator or computer software is the easiest and most effective way to do so. Nonetheless, this is formula provided by Wickham:

Subtract the mean from each score in the distribution.

Square the resulting number for each score.

Compute the mean for these numbers. This figure is called the variance.

Find the square root of the variance.

Probabilities are effective when dealing with lottery numbers, traffic accidents or fatal illnesses and generally come down to ratios. Formula provided by Wickham:

Deaths per 100,000 people = (Total deaths ÷ total population) x 100,000

Journalists should remember that not every person is at the same risk to die of a certain disease fore example. For more accurate probabilities, populations should be divided into risk groups such as age.

Example problem:

Student A scored in the percentile for an entry exam. 95 students took the test but only the top 25 students will be admitted. Did student A make it?

Answer:

45 = x ÷ 95

According to Wickham, the unemployment rate is defined as “the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed and actively seeking work.” The labor force consists of everyone over the age of 16 who has a job or has looked for one in the four weeks prior. Employed means that someone has done work in the past week before the survey and been paid for it. The government doesn’t survey every person, instead using a group of 60,000 households called the Current Population Survey. The Bureau of Labor Statistics take seasonal employment changes into account. Formula:

Unemployment rate = (unemployed ÷ labor force) x 100

U.S. inflation is measured by the Consumer Price Index, which in turn is determined by the price for a basket of certain goods. BLS employees collect CPI data by visiting retail and service business monthly. The CPI is sometimes reported as an index number. The base CPI of 100 was created in 1984, so a CPI of 180.8 in 2002 would indicate a 80.8 percent increase in prices for tracked items. Wickham provides the formula for calculating the monthly inflation rate:

Monthly Inflation Rate = (Current CPI – Prior Month CPI) ÷ Prior Month CPI x 100

For the inflation rate:

A = Annual Inflation Rate

B = Current month CPI

C = CPI from same month in previous year

A = (B – C) ÷ C x 100

Inflation can be adjusted for to compare prices more accurately using this formula:

A = Target year value in dollars

B = Starting year value in dollars

AC = Target year CPI

BC = Starting year CPI

A = (B ÷ BC) x AC

Wickham defines the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as “the value of goods and services produced by a nation’s economy.” It is usually an indicator of how well the economy in any given country is doing. Real GDP takes inflation into account. To calculate the GDP, use this formula:

C = consumer spending on goods and services

I = investment spending

G = government spending

NX = net exports (exports minus imports)

GDP = C + I + G + NX

Real GDP per capita measures goods and services produced per person and indicates living standards of a population in a country.

The trade balance refers to the number of good imported vs. the number of good exported. Formula:

Trade balance = Exports – imports

Example problem:

The IBM ThinkPad 600X had a starting price of $4100 in 1999. How much is that in today’s money if the CPI was 166 in 1999 and 240 in 2017?

Answer:

($4100 ÷ 166) x 240 = $5927.71

Polls and surveys can be deceptive at times and it is a journalist’s job to guide readers through them. Wickham defines polls as an “estimate of public opinion on a single topic or question.” Like surveys, they are often based on representative samples, although the latter usually includes multiple questions. How randomly a participants are selected can play a significant role in the credibility of a poll. Other things to consider include:

Wickham names these formulas for selecting samples:

“Margin of error indicates the degree of accuracy of the research based on standard norms.” It is expressed as a percentage and based on the size of a randomly selected sample.

The confidence level is more a more arcane concept but according to Wickham, it basically refers to the percentage at which the researchers have confidence in the results of their research. It is determined in advance and falls at 90 percent, 95 percent or 98 percent. At a 90 percent confidence level, there is a 10 percent probability that the results occurred by chance. Reporters should always include the confidence level alongside the margin of error.

A z score shows how far off a figure is from the mean and is useful for comparing data that would otherwise be hard to compare in its raw form. Formula for the z score:

z score = (Raw score – mean) ÷ standard deviation

Example problem:

You are conducting a study on music majors and decide to sample students enrolled in a theory of music class. What kind of sample is that?

Answer:

Cluster sample. It is defined by sampling in one defined area or region.

Business beats are filled with maths. Reporter need to understand the basics before tackling press releases, annual reports and quarterly earning reports.

P&L stands for profit and loss statement and Wickham says they are one of the most important documents a company issues because it shows whether the company is making money or not. This is done by subtracting expenses from income.

The cost of goods sold refers to the direct expenses such as through buying products, whereas overhead refers to indirect expenses like rent. The gross margin is the difference between the cost of goods sold and the selling price. Formula:

Gross margin = Selling price – cost of goods sold

Gross profit = Gross margin x number of items sold

Net profit = gross margin – overhead

The balance sheet is another document that shows the financial stability of a company. Although companies use different terms for their balance sheets, generally, the assets side of the balance always equals the liabilities and equity side.

Wickham offers an list of example terms and definitions:

Ratios are used to compare companies against another and are used by analysts to determine things like market value. Reporters should keep in mind that rations are limited to to indicating a company’s strengths or weaknesses only. Using industry standard rations will make it easier for your readers to do their own comparisons. Wickham provides the following formulas:

Current ratio = current assets ÷ current liabilities

Quick ratio = cash ÷ current liabilities

Debt to asset ratio = total debt ÷ total assets

Debt to equity = total debt ÷ total equity

Return on assets = net income ÷ total assets

Return on equity = net income ÷ equity

Price-earnings = market price/share ÷ earnings/share

Example problem:

In order to sell 10.000 laptops, Lenovo has to spend money on the following components and services:

- Research and development: $1.500.000

- Electronics: $500.000

- Advertising: $1.000.000

- Assembly: $800.000

- Quality control: $100.000

What is the gross margin if each laptop is priced at $999?

Answer:

Overhead = add costs for components/services = $3.900.000

$9.990.000 – $3.900.000 = $6.090.000

Jack MacKenzie speaking in front of a COM310 class at Elon University.

By Oliver Fischer

Oct. 6 2017

An excellent resume may not help you stand out from the crowd, but showing personality and initiative might. “If you can’t make yourself interesting you might struggle,” Michael Clemente said.

Clemente is a network news executive who shared advice during an Elon reporting class about the field of communications alongside television news consultant Ken White and vice president of Penn Schoen Berland, Jack MacKenzie.

White works with individuals to improve their storytelling and writing skills, while MacKenzie specializes in communication strategies for corporate, political and entertainment clients.

The landscape of news media is changing in favor of younger people seeking to enter the communications field. “There are opportunities galore,” White said. “You have skills that present staff don’t have.”

Older generations are finding it hard to keep up with the increasing importance of social media in the newsroom. “You would be a welcoming relief,” White said. “People like me look for people like you,” Clemente said.

“If you’re a journalist of any type, you’re a first class passenger.”

- Ken White, television news consultant

Storytelling for the news can sometimes be challenging and slow down the writing process. Clemente said that reporters making slow progress should consider the basic elements of their story. “It’s thinking clearly and making it interesting and putting it down on paper.”

Ken White and Michael Clemente sharing advice about the field of communications.

Reporters should not fall victim to click-bait storytelling that warps the truth to get attention. “That’s the problem with the Vice or some of these other places,” Clemente said. “It might have a kernel of truth, but then they blow it into something that I can’t stand by a few days later.”

Being a journalist also means carrying a lot of responsibilities. “If you’re a journalist of any type, you’re a first class passenger,” White said. It is also more important than ever to provide context in your stories. “Context is more king than content itself,” he said.

White said that news media tend to serve the wrong audience and sometimes forget to follow basic news values, such as being more critical of the 2016 presidential election candidates. “You gotta be aggressive,” he said. “You really gotta hold elected officials accountable.”

Simply covering what happened is not always enough either according to MacKenzie. “Don’t cover the process, cover the news.”

MacKenzie said there are three essential traits you need to succeed in the field of communications.

Apart from that, MacKenzie’s advice was to read a lot and show that you are knowledgable. “Say something they don’t expect,” he said.

In the following video, MacKenzie explains the disparities between the reporting of local news stations and the community that surrounds them.

You must read good writing to become a good writer. Journalistic writing is a world of its own, but no matter how arcane it may appear, there are rules and techniques that can be learned through mere observation. In the following post, I will look at 5 different types of newspaper writing from “America’s Best Newspaper Writing” and discuss some of the following aspects and how they play a role in making that particular news piece great:

Leonara LaPeter

Writing on a deadline is familiar to every reporter, but LaPeter didn’t let herself be thrown off by the ticking clock. While covering the court case of Jerry Scott Heidler, who murdered the Daniels family, she took note of every small detail. A vivid image pops into the mind of the reader when Heidler “didn’t say anything but wiped his nose on his blue and green polo shirt and folded his hands in his lap.”

LaPeter also does an excellent job at forging character by diving into the backstory of Heidler, uncovering further details and anecdotes such as a small mouse that Heidler would carry with him when he was 11. He would always say “come on lil’ mouse, come on lil’ mouse”. He feared the dark and dreaded the curious scenario of a knife coming through the ceiling and cutting him.

Through characters, scenes, dialogues and short transitions, LaPeter is able to turn the court case into a captivating narrative, one that explores both sides of the story and creates sympathy for both the perpetrator and the victims. We feel sorry for Heidler’s sister, who said “I don’t want them to kill my brother.”

By uncovering the troubled past of Heidler, we gain a better understanding of the situation. At times, we might even side with Heidler, thus contrasting the emotions that accompany the beginning of the article, where the death of the Daniels family is outlined. LaPeter achieves a more emotion-evoking tone through variations in the length of her sentences. The resulting rhythm counters the monotonous stereotype of court cases.

Peter Rinearson

One of many roles that journalists fulfill is translating technical language into something that is more easily understood by the general public. Rinearson’s article on how the Boeing 757 was designed is an excellent example of such a piece. Right off the bat, he anthropomorphizes the jet plane as a celebrity that turns heads, thereby easing the reader into the article with a familiar picture, while also emphasizing the importance of the aircraft without resorting to technical specifications.

Despite the topic, Rinearson doesn’t skip quotes and puts real people at the center of his story. As such, he introduces the airline’s president in the second paragraph and uses narrative techniques to turn his article into a story with human-interest aspects. For example, he describes a gate agent’s struggle with the door. “Grasping the door firmly, while the top brass of Boeing and Eastern looked on, she pushed and pulled”.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Rinearson’s article is how he interweaves technical specifications with storytelling. Tech specs and facts regarding the 757 are being carried by the the words, becoming second to the storytelling while not losing their informative nature. “The 323-pound door moved only a few inches. It wouldn’t budge beyond that.”

Throughout the article, details of the effort and consideration that went into the aircraft’s design are sprinkled across sentences, playing a seemingly secondary role to the quotes of people and the narrative, but still informing the reader about technical aspects in a non-threatening manner that is easily understood. At the core of the article still lies the skeleton of journalistic writing, focusing on the struggles that the engineers faced while designing the aircraft and lending a critical tone to the voice, as is expected in journalism.

As Rinearson states himself, “the engineering details of the 757 far exceed the grasp of any single human mind”. He instead resorts to exemplifying problems by focusing on the smaller parts, such as the door. Using metaphors, like comparing the door to a bathtub stopper, is a further example of how to convey a more complex topic to the reader, without losing the nuances of the story.

Cathy Frye

Instead of cutting to the chase, Frye decided to build a narrative style introduction. Despite being longer than a typical lead, it still works because of the suspense that is built in the first few paragraphs.

We suspect what might have happened, but details of Kacie’s story are only revealed in later paragraphs, compelling the reader to continue reading and become more invested in the story. As it progresses, more and more details emerge, such as 13-year-old Kacie Woody’s affinity to online boyfriends, being home alone on the night she was kidnapped and the fight with her friend Sam.

Every snippet of information that is revealed paints a picture looking more and more bleak for little Kacie. In fact, it’s easy to forget that Caught in the Web: Evil at the Door is a news article. It reads more like an example of narrative writing. The inclusion of the chat history reminds the reader that it’s not just a story though. What happened was real.

Despite the sense that Kacie’s story will end badly, the reader is willing to experience the journey along with the characters. The narrative writing is able to transport the reader to Kacie’s home in the “chilling darkness” of that fateful night. Every time Frye paints a new a scene; the counselors office, the computer or the school bus, we feel like we are there, experiencing the story as it unfolds.

As such, Frye chose a chronological approach, rather than the usual inverted pyramid. This approach works for this story. It’s the first in a series of articles and after reaching the end, I wanted to know what exactly had happened to Kacie. I had to consult Google, but this demonstrates the power of narrative writing when the content is appropriate and the writing is superb.

The story is also an attestation to Frye’s persistence, as it took her a great deal of effort to convince the Woody family to disclose all the details necessary for such a holistic approach to the story. Warning of the dangers of online stalkers also gives the story a purpose, thus serving the public just as good journalism should.

Donna Britt

Britt’s article about the cultural phenomenon of frivolously calling women “bitch” reads like a trip through her mind. It’s very personal, resorting to “I” in the first sentence already, as she described her encounter with a teenage girl that wore necklace with the b-word written on it.

At this point, she asks herself why. Rhetorical questions such as this appear several times in her opinion piece. It makes use think. Think about an issue that might otherwise go unnoticed. They serve as a spark for us to contemplate how easily we throw around terms like “bitch”.

She is baffled while the rest of the world seemingly isn’t. And it’s this observation from the personal perspective of an African-American that makes us see something that we might not have considered otherwise. She denounces the brutality of “gangsta rap” and its violence towards women, while pointing out how popular it is.

Britt doesn’t tell us what to do or what to think. She plays through scenarios, fleshes them out and sometimes exaggerates to make a point. Despite her personal perspective, she keeps her distance, never attacking frontally but instead taking opposing arguments and disseminating them, thus revealing her thought process to the reader very clearly.

Britt compares those who say “they’re just dissing the women who deserve it” to white politicians being allowed to use the n-word because they would only be referencing “black people who kill others” or “criminals”. Could you call this hypocrisy? Britt also points out that some women actually like to be called degrading names. It’s these absurdities that speak with clarity, and help Britt to make her argument.

Bryan Gruley

Unlike the other stories in this post, Nation Stands in Disbelief and Horror is a rewrite, drawing from information gathered by over 50 journalist and compressed into a 4.000 word article that was originally 30.000 words in length.

All this was done quickly enough to publish it a mere day the Sept. 11 attacks took place. What may seem like a daunting task wasn’t as difficult for Gruley as you might imagine. Getting the information, i.e. the reporting process, is what’s most challenging.

Despite how spectacular an aircraft crashing into World Trade Center may sound, Gruley did not lead with that. Nor did he mention it in the second paragraph. He only alludes to it in the third. Instead, he leads with people and tells the story from their perspective and how the chaos unfolded in their eyes.

Infographic by Oliver Fischer

In fact, it isn’t until the 5th paragraph that we find what we might consider as the nut graf, outlining that “three apparently hijacked jetliners, in less than an hour’s time, made kamikaze-like crashes into both towers of the World Trade Center and Pentagon”.

Gruley paints a vivid picture of the chaos and gruesome scene that ensued downtown Manhattan with “strewn body parts, clothing, shoes and mangled flesh, including a severed head with long, dark hair”. Again, these telling details transform information into a scene that we can experience as though we were actually there.

From a recent call to Honor. Taken by Elon University’s communication office.

By Oliver Fischer

Sept. 4 2017

Honesty, integrity, responsibility and respect. These are the core principles of the Elon Honor code.

The 12th annual Call to Honor ceremony will take place on Sept. 14 in Alumni Gym at 9:40 a.m. and provides an opportunity for incoming students to make a pledge the Elon’s core principles.

This fall tradition allows campus leaders and faculty to share their expectations of students to live by the core principles of the honor code. Students sign their name of the honor code and receive an honor coin. Last year, the members of the class of 2020 received a coin that was inscribed with the word “honor”.

The call to honor ceremony is very important to our community because it reaffirms our contentment to a very important code of conduct and values that reside at the core of our campus community.

- Paul Miller, Assistant Provost

Each class represents a different value and each class president lights a candle on stage to represent the four core values. “These values are the bedrock on which our academic community rests,” assistant provost Paul Miller said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.